Description

From architectural and horticultural flourish to mythological and literary symbol, the ubiquity of the labyrinth as both an aesthetic and a conceptual motif has persisted for millennia.

While the labyrinth’s earliest documented appearance actually described a convoluted underground structure in Twelfth Dynasty Egypt c. 1800 BC, later manifestations bore a closer resemblance to the gamified structure with which we now associate the term—one incarnation being that of the printed maze.

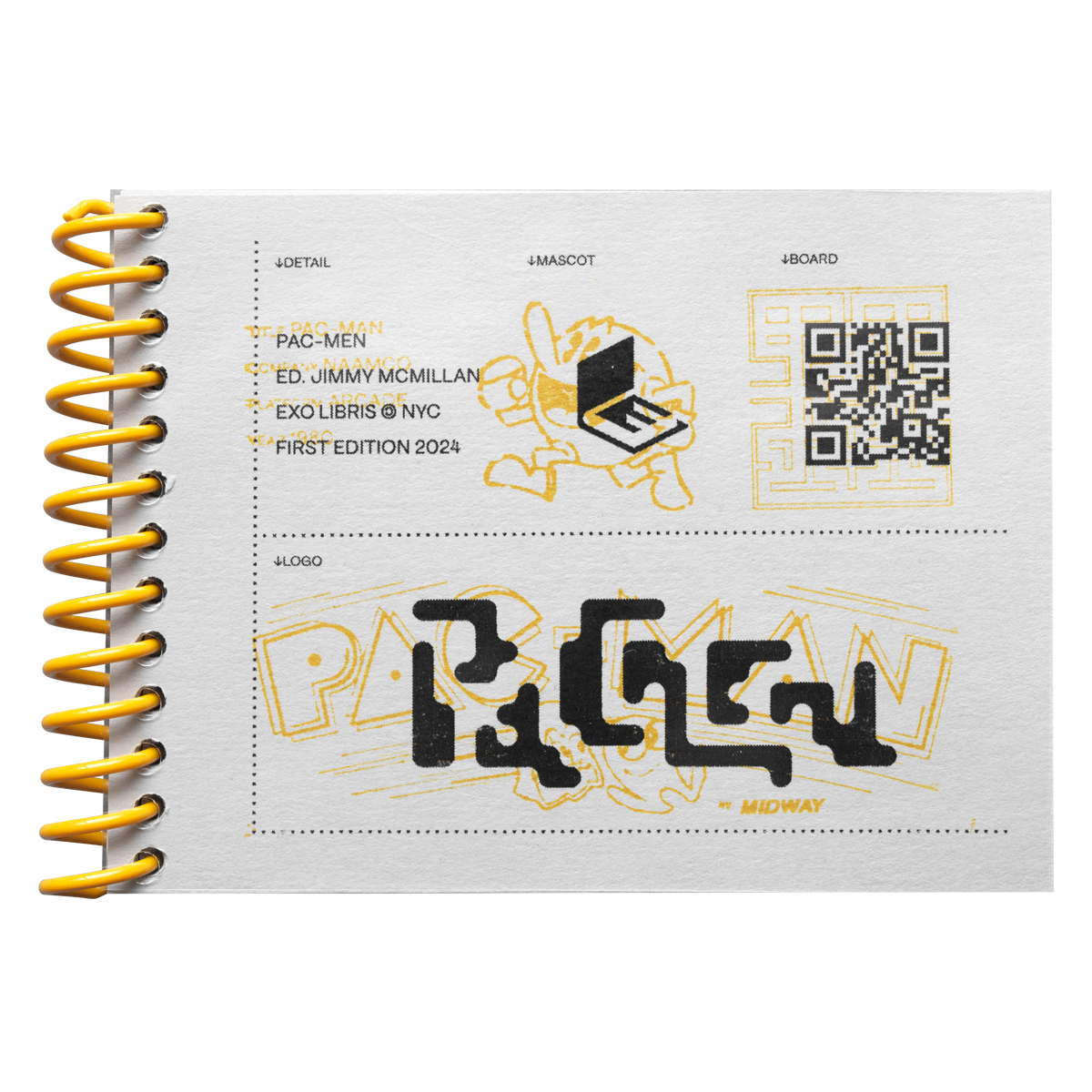

Dating back to Renaissance sculptor Francesco Segala’s early pictorial mazes, the printed labyrinth has remained a mainstay pastime for centuries. And as the second half of the twentieth century ushered in the video game era, the labyrinthine maze board saw a bevy of electronic translations—but none were as successful as Pac-Man.

Pac-Man was a global phenomenon upon its 1980 arcade release. Gamers from Japan to the US were entranced by the yellow pill-popper as they led him through snaking strings of pixelated pearls. The title spawned a new genre of interactive entertainment called “‘dot-eat’ games (ドットイート)” in Japan and “maze chase games” in the United States1, which spurred both distant derivatives and carbon copies alike—though some may have been more altruistically minded than others.

|

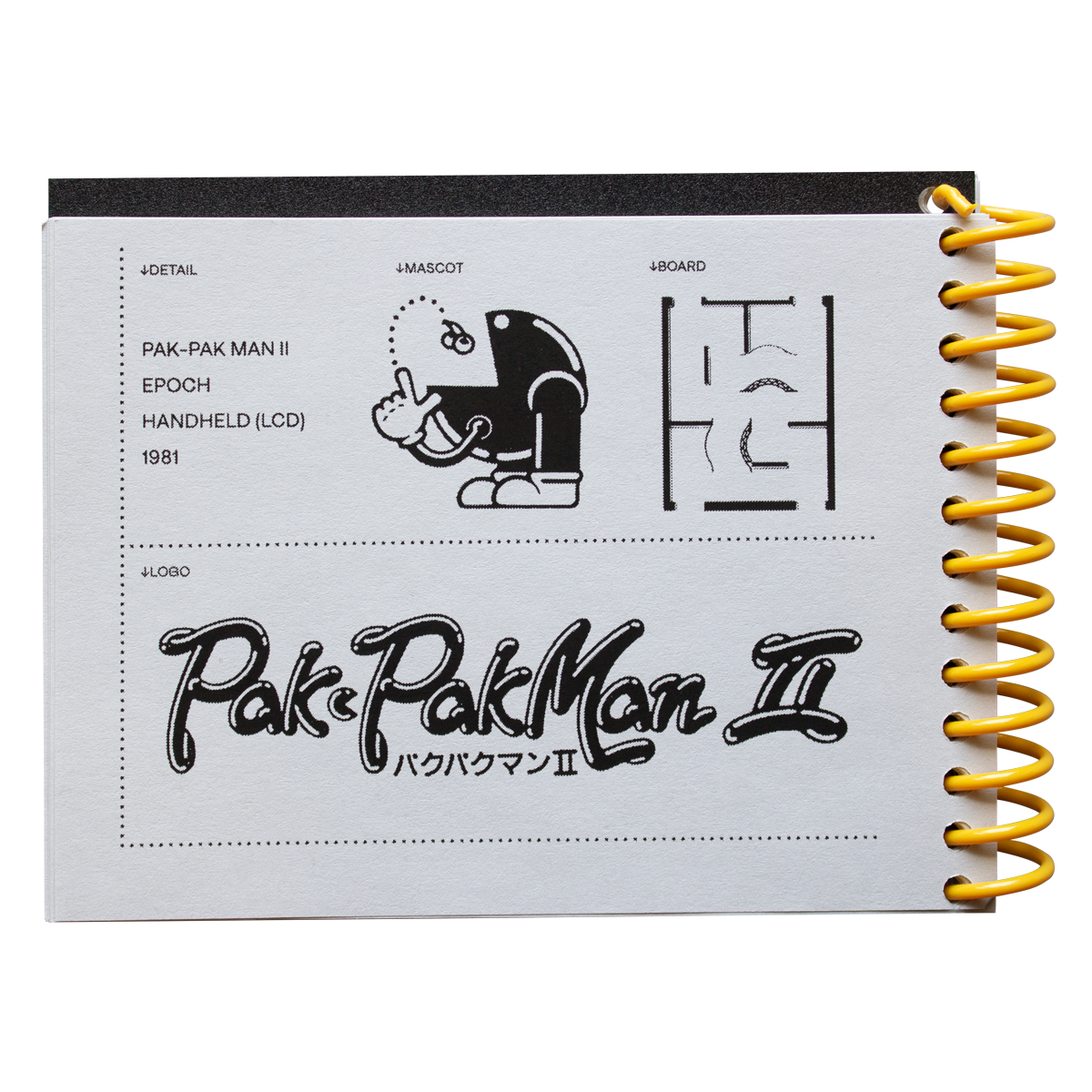

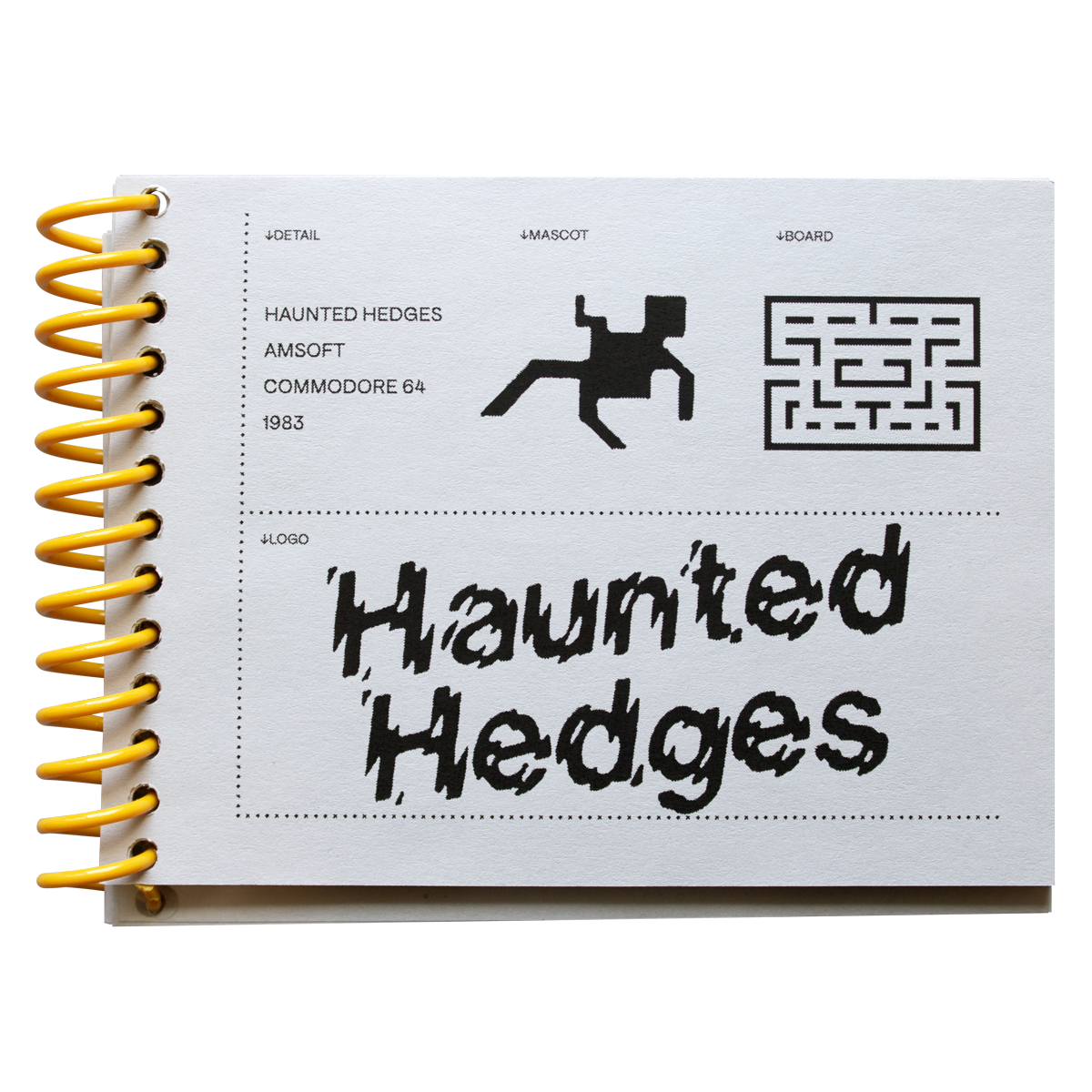

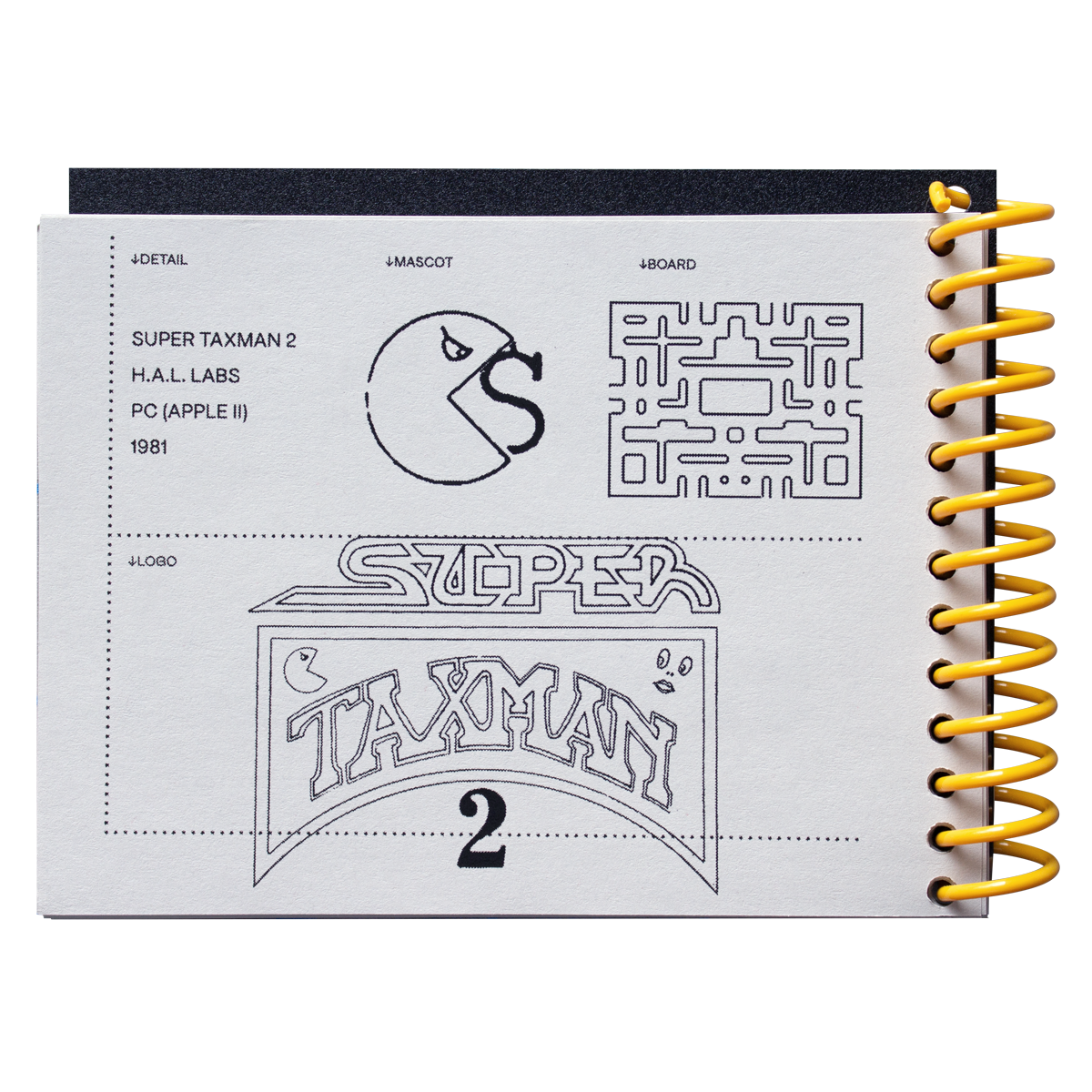

Select mascots from Pac-Man knockoffs and clones, clockwise from top left:

Sprite Man (C64), Mystic Man (Arcade), Pac Pac (Arcade), Dot Gobbler (C64), Snakman (C64), Gnasher (ZX).

A key tenet of the hacker ethic has always been the democratization of data: “a free exchange of information, [ideally] in the form of a computer program, allowed for greater overall creativity,”2 Steven Levy wrote in Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. He elaborated:

“To a hacker, translating [a] program from one machine to another was inherently good. The idea that someone could own Pac-Man, that clever little game where ghosts chase the dot-munching yellow Pac-Man, apparently was not a relevant consideration to John [Harris, developer of an unlicensed Pac-Man port for the Atari 800].”3

But it was a consideration for publishers like Atari and Midway, Pac-Man licensees for the Atari console and American arcade, respectively—the former was notably “ironic in retrospect [as] Atari [initially] turned down the opportunity to license Pac-Man [for US arcades] from Namco.”4

|

Above: Copyright Infringement notice as published in Play Meter, Vol. VII, No. 14, August 1981.

Levy summed, “Atari felt that its purchase of the Pac-Man license entitled it to every penny to be earned from home computer games that played like Pac-Man.”5 Legal efforts, however, proved more labyrinthine than Atari’s or Midway’s legal teams originally anticipated.

As Karen Armstrong wrote in A Short History Of Myth, “A myth often happens just once yet also happens all the time.”6 The tale of Theseus and the Minotaur invokes a single event that has since been recounted, recast, and referenced in perpetuity; the corresponding motif of the labyrinth similarly bore singular importance as setting within its origin story, and persists in both aesthetic and architectural capacities today.

|

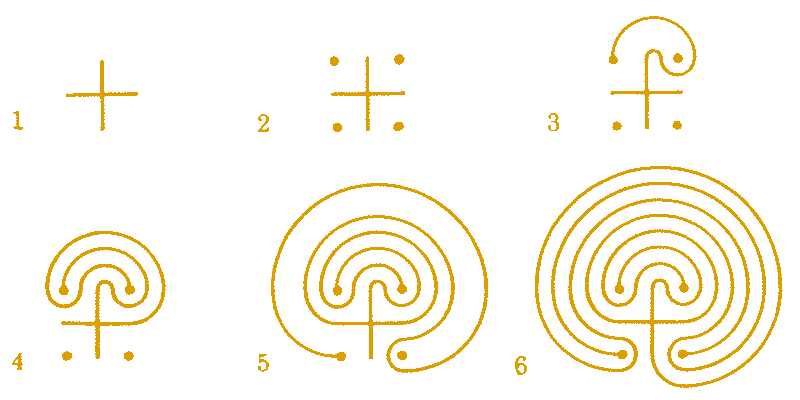

“Diagram showing the construction of the seven-ringed ‘Classical’ or ‘Cretan’ type of maze design.”7

Etymologically, maze and labyrinth “signify a complex path of some kind, but when we press for a closer definition we encounter difficulties,” W.H. Matthews said in Mazes & Labyrinths: Their History & Development.

“We cannot, for instance, say that [a labyrinth] is ‘a tortuous branched path designed to baffle or deceive those who attempt to find the goal to which it leads,’ [as that] ignores the many cases [in which] there is no definite ‘goal.’”8

What can be said of mazes and labyrinths is acknowledgement of their historical ubiquity, in contexts both publicly ceremonial and privately meditative: from the Game Of Troy in Ancient Rome, to the games that emblazoned gravestones and cathedral floors in Medieval Europe.

|

|

Left: Etruscan wine vase with “Truia” and labyrinth engravings, ca. sixth or seventh century B.C., Wilhelm Deecke 1881.9

Right: Danish Runic stone cross with labyrinth figure, Ole Worm 1643.10

And within this broader cultural context exists a “combination of the Cretan and the modern labyrinth where Ariadne’s thread has to be eaten up by Puck Man (as the figure originally was called in Japan) in the maze, which is monitored by the player.”11

|

Top: Graffiti found at Pompeii (National Archaeological Museum, Naples).

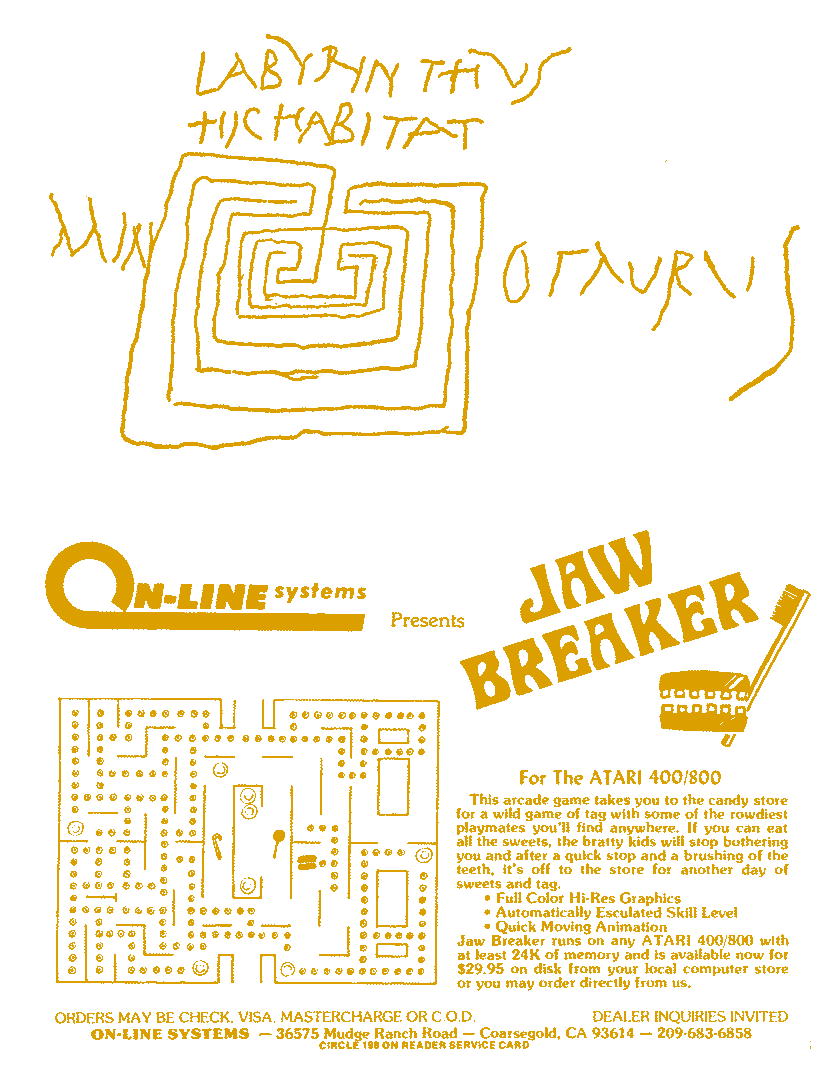

Bottom: Jawbreaker computer game advertisement (Creative Computing, October 1981).

By the time John Harris and his publisher On-Line Systems were sued by Atari, their Pac-clone boasted unique sprites, new game dynamics, and a fresh title: Jawbreaker.

“[The] line between creative freedom and plagiarism got fuzzier and fuzzier.” Harris’ defense successfully argued “that John Harris had simply taken the idea of Pac-Man from Atari, and cited law which stated that ideas are not copyrightable.”12 Once the suit ended in favor of Harris and On-Line Systems, Atari expressed their interest in licensing Jawbreaker. Levy called the case “a challenge to the Hacker Ethic”: “Did the public benefit from one company ‘owning’ a piece of software and preventing others from making it more useful?”13 Especially when, in the case of Pac-Man, its very interface is already so formally indebted?