Description

Beyond the laundromat and the parking meter, quarters don’t see much action these days. The payphone is virtually extinct, as is the cigarette dispenser…and the condom machine.

But while the payphone’s increased obsolescence was a natural byproduct of advancements in mobile telephony, scarcity of both cigarette and condom machines was borne out of increased awareness over their contents’ side-effects: cigarettes saw increased prohibition as research detailing adverse health effects mounted, whereas condoms were distributed more freely in response to their more widely accepted medical benefits.

Unlike big tobacco, however, the American condom industry saw ethical and legal woes from its outset. And yet, it’s from this origin that condoms found an apt partner in the coin-op dispenser from which they were once sold.

Variously employed to aid or abate illegality, the vending machine was an ideal sales format for the condom, affording visual real estate for creative and coy logos and graphics—selections of which are documented in this miniature publication.

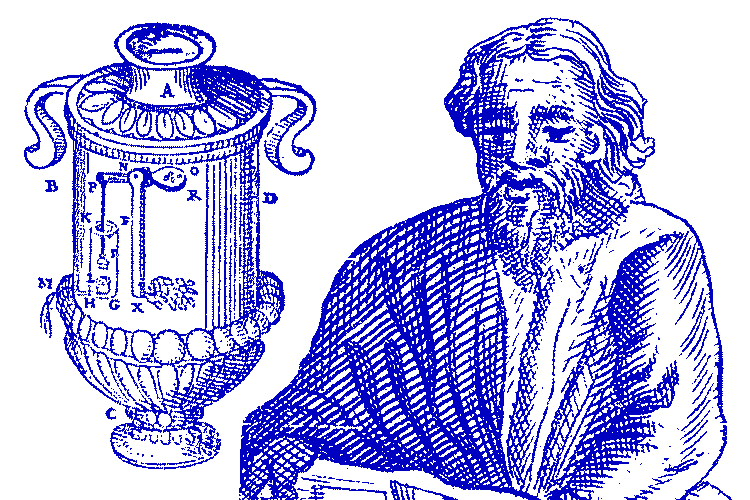

The vending machine was first documented by the ancient Greek academic Hero of Alexandria.

|

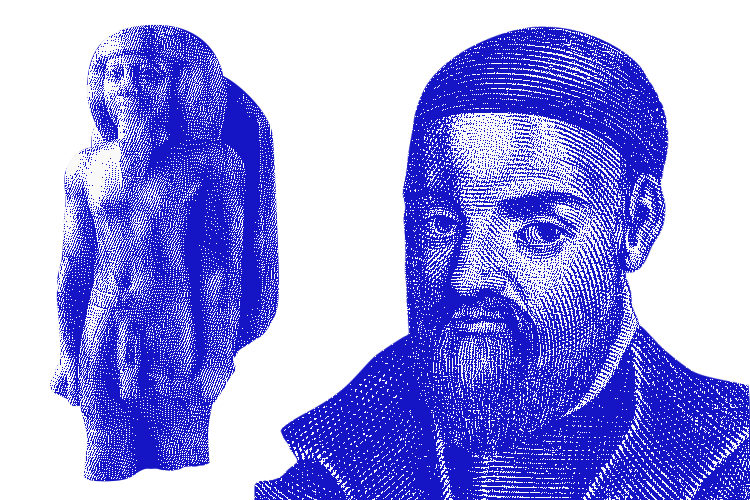

Left: Diagram of Hero’s Holy Water Dispenser; Right: Hero Of Alexandria.

Described in Hero’s Pneumatika (c. 62 CE) as a “sacrificial vessel which flows only when money is introduced”1, its inventor was never documented, and “it was also unclear if any were [built].”2

Still, Hero’s pay-to-pray holy water fountain was the only recorded vending machine for millennia. Unlike the first machine’s speculative nature, the second one was real—and sold smokes.

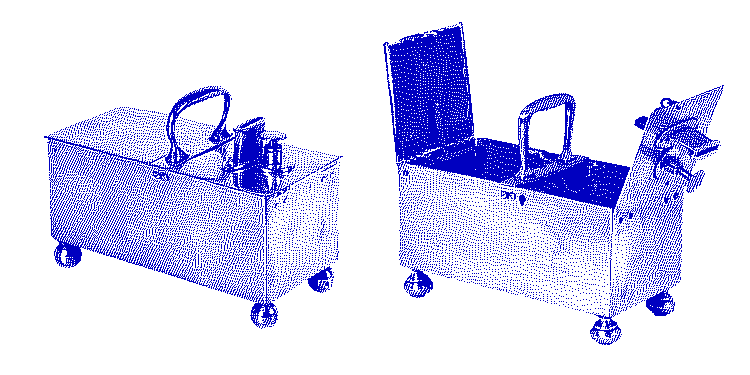

|

Above: Snuff box, closed and opened.

Tobacco dispensers called “snuff boxes” began to service English taverns as early as ~1615 CE. Their function was simple: at the drop of a coin, the lid of the snuff box unlocked—allowing buyers access to the snuff tobacco parcels within.

The vending machine’s final prototype graced the exterior of a British book shop in 1822: in the midst of censorship by authorities, free speech-defending publisher Richard Carlile devised an idea intended to avoid identification: a “coin-freed book vending machine attached to the front of his shop”3, meant to obscure the faces of his staff.

|

Left: an illustration of Richard Carlile’s bookshop; Right: Richard Carlile.

In the decades that followed, coin-op vending took off as a sales format, on both sides of the Atlantic: the second industrial revolution gave cities an influx of commuters, and vendors a new sales tool.

As Nic Costa explained in Automatic Pleasures: The History Of The Coin Machine, “introduction of coin-freed machines during the last quarter of the 19th century [echoed broader shifts in] Western society during this period.”4

Vending machines soon met nearly every consumer need: snack and drink dispensers quenched hunger and thirst; newspaper-vending machines informed readers; dispensers of wine, liquor, cigarettes, and cigars indulged buyers’ vices.

As Kerry Segrave noted in Vending Machines: An American Social History, however, “less available [were] condoms.”5

The condom’s earliest ancestor (c. 1350 BCE) was neither a prophylactic nor contraceptive: Egyptians of the Twelfth Dynasty wore “linen penis sheaths” [as talismans meant] “to promote fertility”6.

Thirty centuries passed before condoms were first documented as prophylactics, by Italian anatomist Gabriello Falloppio in De Morbo Gallico (1564).

|

Left: a sculpture depicting an Egyptian figure wearing a penis sheath; Right: Gabriello Falloppio.

It was the 1839 discovery of rubber vulcanization by Charles Goodyear, however, that catalyzed the commercial condom as it’s known today.

Although American factories began to manufacture condoms in the 1850s, their domestic distribution was nearly brought to a halt in 1873.

Anthony Comstock believed that “impure thoughts and behavior [were as sinful] as lack of faith”7 and in 1866, found his true calling upon relocating to America’s de facto sex capital.

New York City was once known as the “Gomorrah Of The New World”: the still-nascent metropolis boasted a carnal cottage industry of nude models, prostitutes, and vendors of pornographic printed matter and illicit condoms.

Seeing a commercial industry that relied on the US postal service for distribution, Comstock lobbied for legislation that outlawed the shipment of “any article [preventing] conception”8.

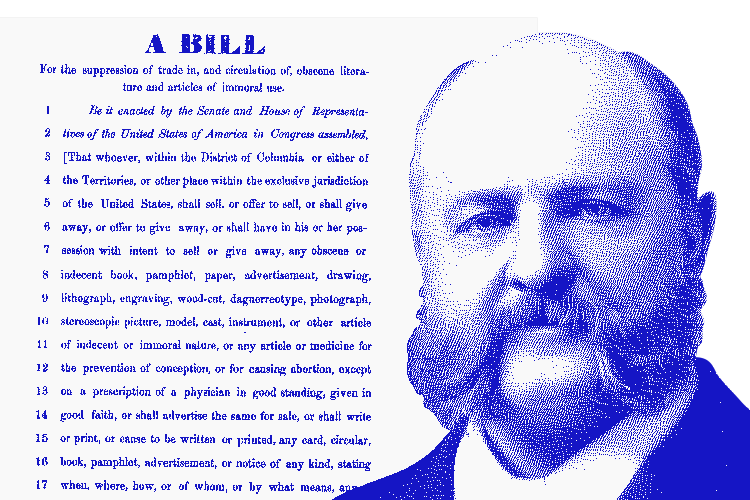

|

Left: An excerpt from Anthony Comstock’s bill; Right: Anthony Comstock.

The Comstock Act, embedded in a broader postal bill signed into law in 1873, effectively banned the sale of condoms nationwide.

Its side-effects climaxed during the first World War: condoms were excluded from soldiers’ rations. By the end of the war, a million dollars was spent to treat the 380,000 US soldiers that contracted STIs.

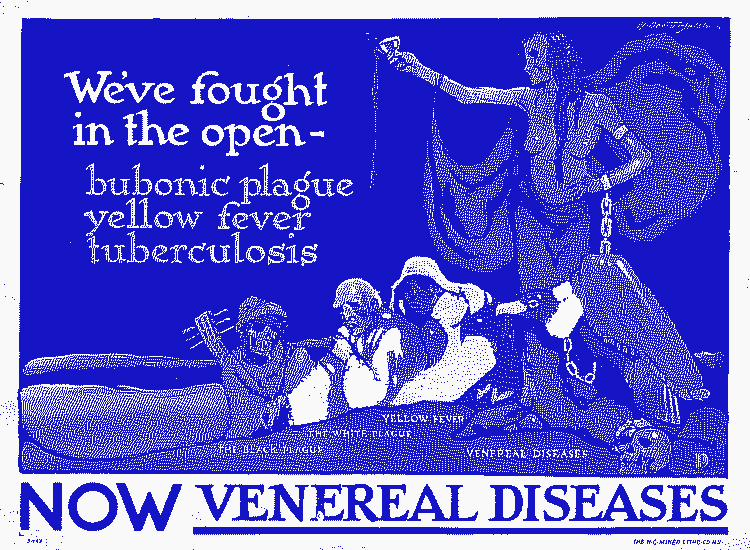

|

Above: An example of venereal disease-focused public service artwork printed during World War I.

The fiscal and medical fallout precipitated repeals: the first of the Comstock Act’s many bylaws were reversed in 1918. Condoms were finally legal again. Soon, condoms were “familiar sights [in] a host of male commercial venues”9.

Enter: the condom machine.

The coin-operated condom vending machine was the brainchild of Polish-German innovator Julius Fromm who, in 1928, “succeeded in his ongoing efforts to install the first [machines]”10*.

|

Above: Julius Fromm.

But overt stateside adoption lagged, due in part to local “mini-Comstock”11 regulatory hurdles: in 1934, the Detroit “city council [banned] contraception in coin-operated machines”, while the New Jersey State Supreme Court “[limited] the right to dispense [condoms] to physicians and druggists”12.

Staggered re-legalization of condoms in America was evident not only by descriptions of the products as “for the prevention of disease only”—a holdover from the Comstock era—but on vending machines too:

|

Above: The faceplate of a condom-vending machine, advertised ‘for the prevention of disease only’.

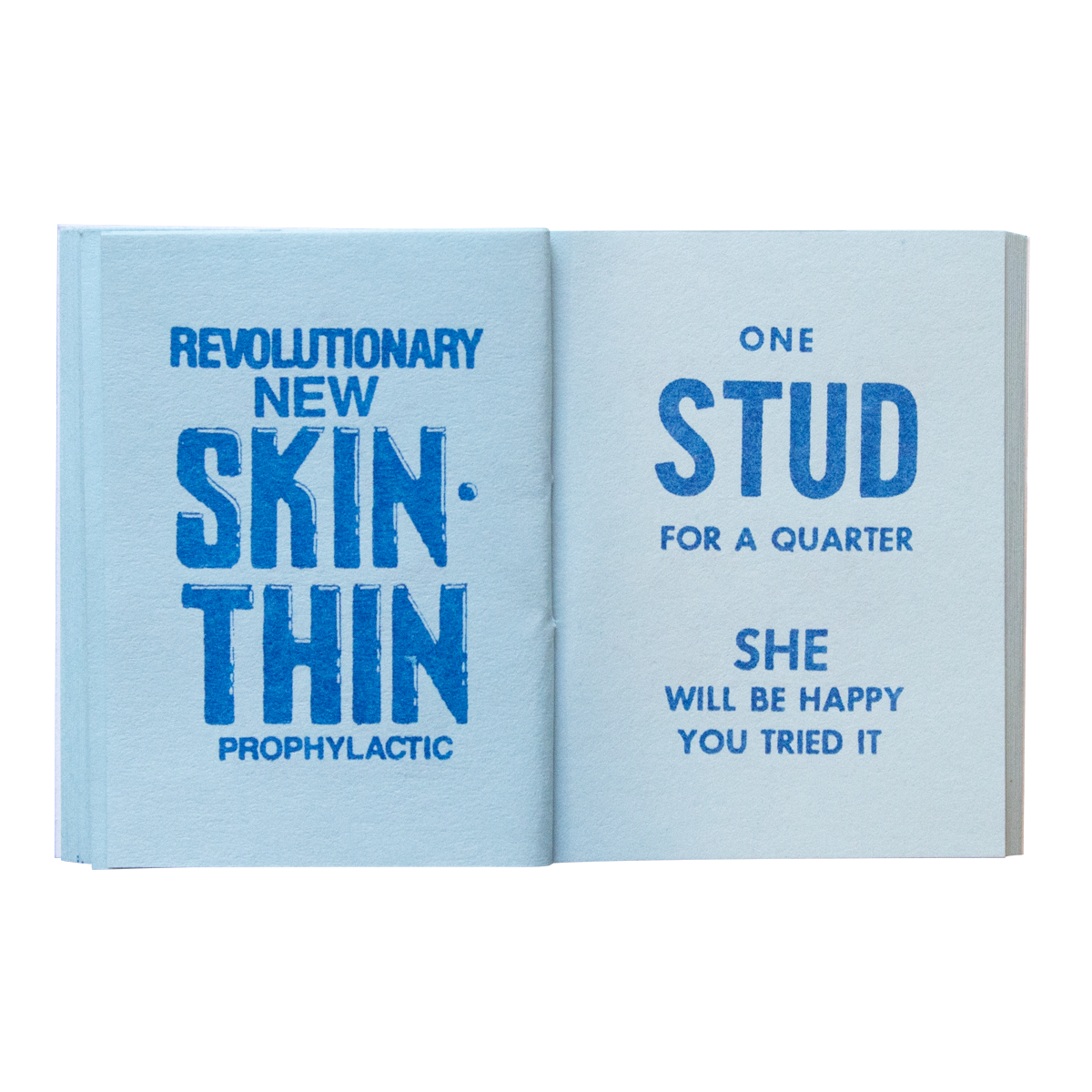

While store-bought condoms from Sheik to Mermaid adopted racy images and language, early condom machines favored the covert, barely alluding to the true purpose of their “personal hygiene” wares.

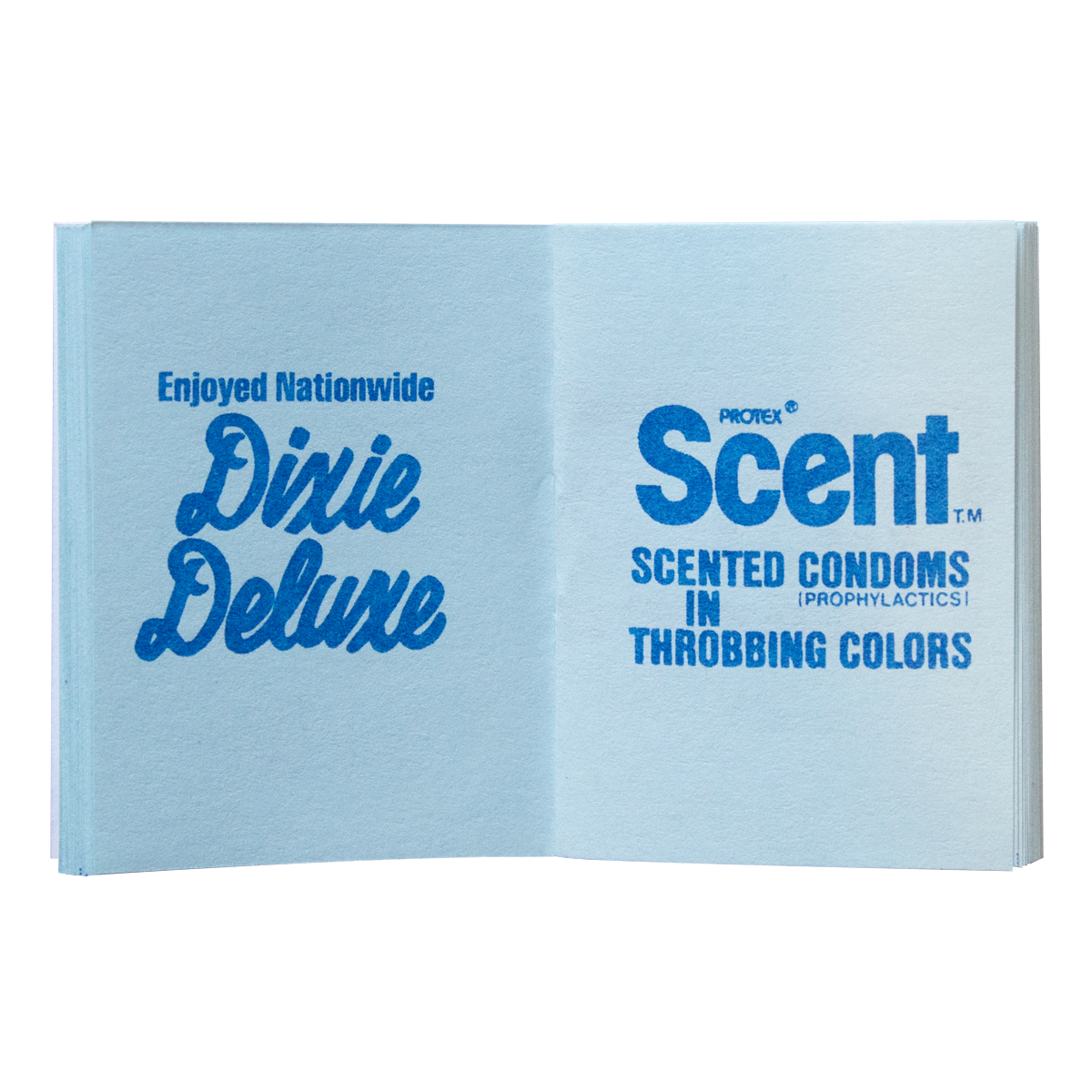

But regulations eventually eased, and so did ad language: “electronically tested” and “ultra modern” gave way to “pleasure dots”, “raised ridges”, “ticklers”, and “tinglers”.

Soon, novelty condom machines offered a rainbow assortments of textures, tastes, and scents.

But the 1980s onset of HIV/AIDS renewed the urgency of safe sex, which spurred other shifts: condoms finally shed their remaining social stigma. Their resulting retail ubiquity made condom-vending machines all but redundant. Similarly, the medical merits of condoms regained their selling strength—cementing novelty’s place (mostly) in the past.